About two months ago, as I hurdled down the highway to my parents home in Missouri, the BBC History Extra Podcast filled my road trip. Historian Annie Gray spoke the host, answering questions from her last podcast about the history of food. She discussed the religious and political origins of vegetarianism, and later veganism, in Europe. As she discussed almond milk, my little dairy-free ears perked. Since listening, I picked up a passing fascination with medieval almond milk.

Rather than California hippies, almond milk’s first craze came from medieval Christians. Some background: Catholics, to this day, observe fasting days where they abstain from meat. Prior iterations of catholic fasting grouped eggs, milk, and any animal by products in with meat. Curiously, sea birds and fish were not meat, hence many Catholics’ weekly filet of fish from McDonalds. In the middle ages, adults were expected to avoid dairy, eggs, and meat on Fridays, Ash Wednesday, most Sundays, and most feast days. Much like our modern love of oat milk, medieval cooks did not view almond milk as a pitiful stand in. No, in fact almond milk became a praised and bountiful ingredient in medieval cookery. Some food historians go as far as calling it the single most important item in the era’s cuisine. The nut-milk showed up in desserts, soups, meat dishes, and drinks. Maybe surprisingly, almond milk was a more popular drink than its dairy – counter part, which was not yet pasteurized or safe to consume.

Like Christianity itself, Almonds long predate their European presence, originate in the near east. The nuts, as they grew in the wild, were initially extremely toxic, and in some parts of the world they have retained their danger. But for the most part, we can attribute our sweet marzipan and granola bars to a mutation occurring in almond trees in the early holocene. After that, between 12,000 and 3000 years ago, humans began domesticating trees, the first of which being almonds. To breed sweeter nuts, farmers would introduce stress to the saplings, blocking the formation of arsenic and amygdalin. Thus, almonds became a snackable commodity.

By the time European’s were living by way of the Didache, almond products were already produced in the Mediterranean. Evidence of this weekly vegan past still present in Spain’s Ajo Blanco and France’s Blanc Mange. Many of the recipes for almond substitutes have fallen by the waysides of history, but they can still be found in medieval cookery manuscripts, if one looks for them

Ein Buch von guter Speise

In my historical almond milk deep dive, I found the site MedievalCookery.com. Here, I found a trove of translated historical cookbooks. In looking through almond recipes, I found Ein Buch von guter Speise, or in English, A Book of Good Food.

The cookbooks is part of the larger House Book of Michael Leone , or the Würzburger Song Manuscript. This 14th century volume comes from the town of Würzburg in Bavaria. This consisted of two volumes, the first volume of poetry now lost to time. The second volume includes songs, prayers, histories, and of course, the first cook book in the German language. The recipes in the collection are, to say the very least, fascinating. In particular, names like “heathen cakes,” “this is also a good one,” and “a good little dish” sound like the makings of the strangest dinner party I could attend.

I found the curious, vegan masterpiece “a good filling,” which roughly creates an almond cheese.

The recipe reads:

“39.q Ein gut fülle (A good filling)

“Nim mandel kern. mache in schoene in siedem wazzer. und wirf sie kalt wazzer. loese die garsten und stoz die besten in einem mörser. Alse sie veiste beginnen. so sprenge dor uf ein kalt wazzer. und stoz sie vaste und menge sie mit kaldem wazzere eben dicke. und rink sie durch ein schoen tuch. und tu die kafen wider in den mörser. stoz sie und rink sie uz. schütez allez in ein phannen. und halt sie über daz fiur. und tu darzu ein eyer schaln vol wines. und rüerez wol untz daz ez gesiede. nim ein schün büteltuch und lege ez uf reine stro. und giuz dor uf die milich. biz daz sie wol über sige. swaz denne uf dem tuche belibe. do von mache einen kese. wilt du butern dor uz machen. so laz ein wenic saffrans do mit erwallen. und gibz hin als butern oder kese.

Take almonds. Make them beautiful in boiling water (Blanch them). And throw them in cold water. Remove the rancid (almonds) and pound the best in a mortar. When they begin to be oily, so sprinkle thereon a cold water. And pound them strong and mix them with cold water smooth and thick. And wring it through a fine towel. And do the pods/husks in the mortar again. Pound them and wring them out. Pour all in a pan and hold it over the fire. And add thereto an egg shell full of wine, and stir it well and (so) that it is boiled. Take a good servant-cloth and lay it on clean straw. And pour thereon the milk, until it drops well over that (Probably means until the whey runs out.), (and) which then stays on the towel. Therefrom make a cheese. If you want to make butter out of it, so let a little saffron boil with it (but this needs to be done when the almond milk is made). And give it out as butter or cheese.“

https://www.medievalcookery.com/etexts/buch.html

These instructions are about par for the course for medieval cookbooks: vague, bizarre, and ultimately not very helpful. But thats okay, right? No one would actually want to make this and eat like a Catholic vegan in premodern Bavaria. Think again.

A recipe for Almond Cheese

Because I have too much time on my hands, I took it upon myself to translate this recipe into something slightly more user friendly.

- Blanch almonds (if you won’t make a bunch of vegan cheese, this means pour boiling water on them, let sit for a minute, then submerged almonds in ice-water.)

- Peel almonds

- Pound nuts in mortar and pestle. While the almonds release oil, sprinkle cold water. Keep doing step five until mixture is smooth and thick

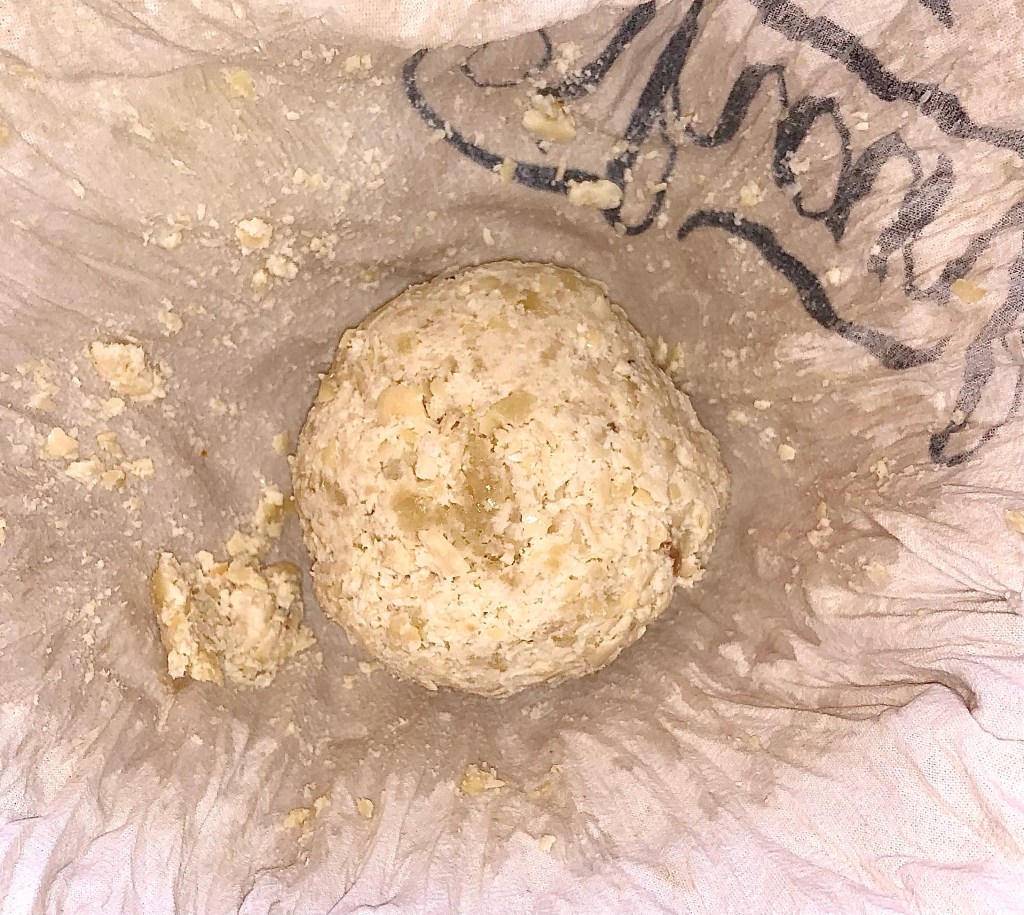

- Wring out with towel until it forms a dry ball of almond mush

- Regrind shells and husks of almonds, wring out, add to almonds (I ended up forgoing this step.)

- Add nuts to pan, heat on medium flame

- Add a third- half cup of wine, stir wine so it heats and boils

- Pour mixture into fine cloth, drain fluid

- Form into cheese

Ingredients

1/4 Lb of Almonds

1/3 cup of “wine” (see below)

about a cup of cold water

cheese cloth

A note on medieval wine: Sources show that medieval wine was nasty. Wine was often thicken with resin, then salted and seasoned with herbs. The vino spoiled far quicker than my Barefoot pinot grigio. As a result, I tried to ruin a glass of wine with white vinegar and salt.

The Process

In general, this process was a lot of work for a pretty lame reward . Maybe it should have put me in the lenten mood of passionate suffering, but more than anything I wished I had some serfs or about 15 children to help me make the almond cheese.

Blanching and peeling the nuts somehow took far longer and far shorter than intended. My hubris quickly became apparently as my arms tired and another cup and a half of almonds stared me down. I ended up roasting the leftover nuts with rosemary and olive oil so I would have something edible to show for the morning. Once blanched, grinding almonds was the hardest mission. I found adding a few at a time helped, but overall, the nuts were, unsurprisingly, hard. The recipe did not call for soaking the nuts, which would have eased the grinding process, but would have lessened the righteous pain of grinding the almonds. Admittedly, if I was a little tougher and a little more pious, maybe I could have beaten the almonds into the smooth consistency I envisioned. I will be honest, 90 minutes into pounding them, I was not emotionally suited to continue.

At this point, I separated the paste into two balls. I mixed a few tablespoons of nutritional yeast, salt and pepper, a little olive bring, and some olive brine into the mix. This was not detailed in Ein Buch von guter Speise, but I figured that after my hours of toil I deserved something slightly closer to cheese.

After squeezing the paste in a clean towel to get rid of some liquid, I transferred it to a hot pan and slowly added in the wine. Something… happened… something scientific, I think. The wine bubbled and absorbed and the paste got the slightest bit slimier and softer. The unseasoned goo went straight into a ramekin. After cooking the seasoned ball of goop, I potted it and topped it with dried dill, rosemary, and basil. A few hours later, the “cheese” was ready.

Taste Test

Well, what did you really expect. I was not that great. The plain, authentic replication of Eine Gute Fuhle tasted exactly like what it was: smashed almonds cooked in the worst wine ever made. The texture was very dry and crumbly, and the wine and vinegar flavor clashed with the sweet nuts. My updated version faired considerably better. The addition of oil benefitted the texture, making it a bit more spreadable. My best description is that if it were cheese, it would be the worst goat cheese ever produced, and the animal should probably be exorcised. However, as a vegan cheese made by an idiot, it was pretty good! I won’t crave it anytime soon, but if a vegan or nun was seriously jonesing for a midwestern-cheeseball, this would do in a pinch.

Are you going to try to make this? Did you know that medieval catholics were some of the OG vegans?